A few months ago, I posted the following impulsive (and slightly kitsch) question on Threads:

“Why don’t everybody and they mama know about Percival Everett?”

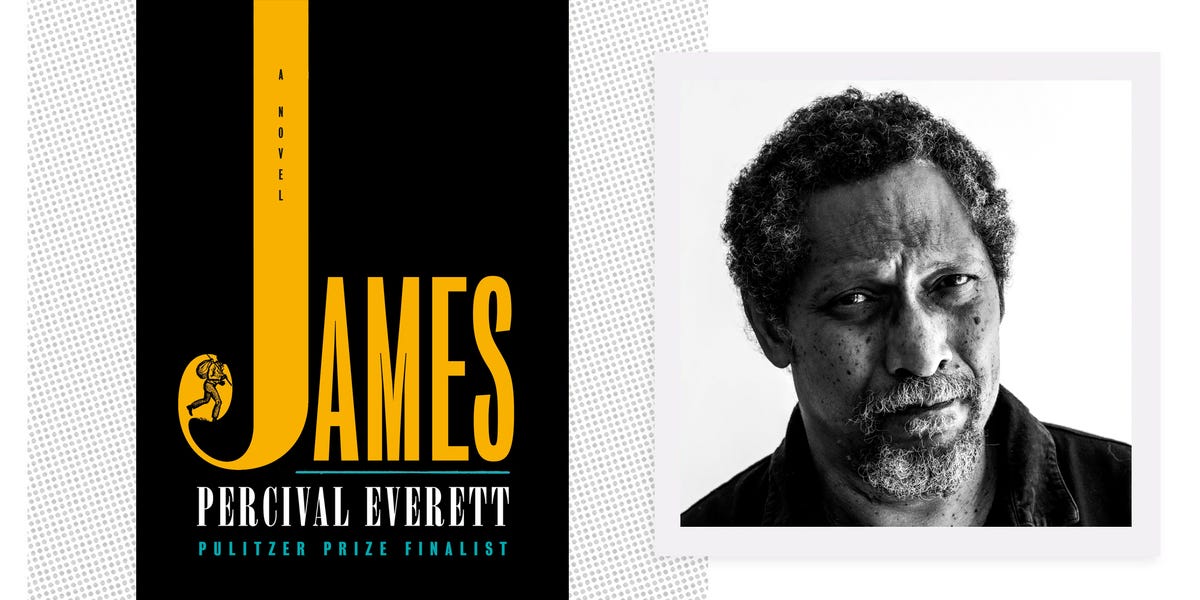

I’d recently finished Everett’s latest feat, James, and was so taken aback that I turned the book over in my hands a few times afterwards, as if the brilliance that I’d just experienced inside the book could somehow be explained on the outside covers. I was preparing to speak to the author at a book conference in a few weeks and was up to my ears in Everett. He’d written 23 novels prior to this one. His 2010 novel Erasure was soon to be released as a feature film entitled American Fiction, with stars including Oscar nominee Jeffrey Wright, Tracy Ellis Ross, and Issa Rae. Everett had recently been on the shortlist for the Pulitzer. I was aghast. Embarrassed. Where had I been? As a professional reader, I’m constantly discovering “new to me” writers and generally have no qualms about it. There are so many good books out there; it would be impossible for me to know all of them. This year alone I found out about such luminaries as William Melvin Kelley and Howard Bloom. They’re different, though: Kelley is famously described as a “lost giant of literature,” so it’s almost expected that I’d stumble upon him only after a significant amount of digging. And Bloom…well, is my life actually better knowing that he wrote things? But Everett—a very alive, very prolific genius—is still giving us stories and brilliance, and I’d had no idea.

Although the swath of folks who are aware of Everett’s body of work might not include “everyone” and subsequently “their mothers,” he is still, despite my daftness, a celebrated and accomplished icon. A literary jukebox. His 2020 novel Telephone was published with three different endings simultaneously. In 2021, he wrote The Trees, a murder mystery that in its own way paid homage to the murder of Emmett Till. He’s written several westerns. His protagonists have been doctors, painters, writers, and a man named “Not Sidney Poitier.” If anyone is poised to casually (after all, he has bills) write a masterpiece that not only becomes instant canon but also sets a brush fire to the current ones it stands upon, it’s Everett. And that’s exactly what he’s done with James.

It’s imprecise to call James a retelling of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. A reimagining doesn’t quite fit the bill either. It really is a re-centering of Jim, Huck’s enslaved companion throughout the novel, and a de-centering of Huck and all of the whiteness, privilege, and oblivion that surrounds him. I had the privilege of speaking with Everett twice about the novel, once during the Heartland Fall Forum book conference in October and again a few weeks ago. The following interview is a marriage of those two conversations.

Why James right now? You have such a prolific body of work. Is a book like this something that just came to be, or do you have a checklist of things you want to try?

It’s complicated. It was brewing for a long time, but I wasn’t smart enough to know what to do. It’s like a volcano; it doesn’t plan to go off. I knew it would happen, but all the pieces had to be there. People ask me all the time, “How long did it take you to write this novel?” and I tell them 66 years. That’s how art works.

You gave us the gamut of enslaved characters. We met Norman, we met Brock, we met our focused friend in the broiler room. Can you tell me a bit more about the characters that you placed throughout James’ journey and the multiple dimensions you gave them?

I’m trying to address a more contemporary view of African Americans. There is this cultural perception, disembodied belief that you can talk about the African American experience as if it is “a” thing. As if it’s not influenced by geography, religion, socioeconomic concern. When I was younger, I was asked, “Who is the leader of it [Black America]?” And that would be completely unintelligible to a white person: “Who is your white leader?” You might get an answer from someone who would say, “David Dukes,” but then, of course, you’d know who you were dealing with. So, in that same way, the institution of slavery had to be a different experience for different people. It’s just a way of trying to be fair to participants in a life.

Who was your favorite character to create?

I hated all of them. You live with people for a couple of years and they become annoying.

I loved James so much!

Invite him to dinner. Sure, there were scenes I liked making. But no, I’m God, and I don’t like them.

Why is it critical that Black people reclaim their narratives?

I’m so sick of slavery novels. What do you say after slavery novels? “Well, I changed my mind”? When I was growing up and went to the bookstore—I read, like most writers, voraciously as a kid—anytime I would look for novels that had Black characters, it either took place in the antebellum south or the inner city. I came from a family of two generations of doctors; we would spend our summers in Annapolis, Maryland, and we lived in Columbus, South Carolina. My family wasn’t there [wasn’t represented in the text], even though I knew my experience wasn’t unique.

I started to understand some of the politics of publishing. And how I mentioned things build and come together over a period of time—that would have been one of the seeds of James. I read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. I love that novel. It’s the first “modern” novel. It’s great. It doesn’t have any deficiencies that I’m addressing; [James] addresses what Mark Twain would not have been able to address. So I got to participate in this discourse. Art is selfish. Anyone who lives with an artist will attest to that. It’s full of contradictions. On one hand, we’re so vain that we expect people to read all of this stuff that we have written. And on the other hand, there is nothing more humbling than the reception of that work.

A strong theme in this book is freedom. Jim regularly grappled with if it was something he could obtain. Can Black people ever have freedom in this country? True freedom?

In this American discussion of “freedom,” there is a distinction to be made between freedom and rights. It’s fairly safe to say that what slaves wanted was to enjoy the same rights as people who were not slaves. And I think that’s still what people want: to be able to drive on the road and not have particular fears because of the way that you look as opposed to the way someone else looks. That we all enjoy the same rights. Once that’s squared away, we can have all sorts of philosophical conversations about what freedom is. I have teenage sons. I am not free. When I ranched, I was not free. I had animals that needed to be fed. That is a philosophical issue that cannot be addressed to anyone’s satisfaction, so I think the conversation in America should be about rights.

What is your writing process?

I put my bills on my desk, and that’s called motivation. I don’t have a process; every book comes differently. The only thing that I know is I research way more than I need to for anything, as a way to not only accomplish work but to avoid it. And if somebody says, “Let’s go to a movie,” I go to a movie. It happens. My students come to me and say, “I have writer’s block,” and I say, “No, you don’t.” They say, “What do you mean?” I say, “There’s no such thing. Write me 50 pages by Friday or you fail.” And I’ll get pages. They might not be good pages, but you can work on bad pages. You can’t work on no pages. And I treat myself the same way.

When we spoke in the past, you mentioned that, as a child, you often thought about Jim even while you were reading long passages [of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn] that solely involved Huck. What was it about Jim’s character that made you wonder about him?

The novel belongs to Huck, and rightly. Huck is dealing with slavery in that American way, which is, “How does this innocent person, who knows that this is wrong, reconcile the fact that the only father figure in the novel for him is property?” But Twain cannot put himself in the position of being a slave, nor in the position of anyone in his family being a slave. That part of the story cannot be there. To anyone with an imagination who is an ancestor of people who were serviced to that condition, I had to wonder what that story might be.

Mark Twain has been flattened by our culture, in part because of the mass banning of Huckleberry Finn, which of course happened because of the flagrant use of the N-word. Despite this, you did this re-imagining/re-telling—and before this, Erasure had a quote from Twain at the beginning. What impactful parts of Twain’s work do we miss with our rush to respectability?

The importance of Huck Finn is it’s the first time that slavery is not the subject of a protest novel. It’s a sincere and legitimate effort at understanding the effects of slavery not only on the enslaved but on the enslaver. Huck is dealing with American trauma that persists even now. There is no American work of art that does not in some way have to deal with this artificial construction that we call race.

In your research of this book, what did you find out about enslaved peoples’ use of coded language and how extensive it was?

Oh, I didn’t find out anything about coded language in that way. It’s just a fact that human beings, especially when they are oppressed and under fire, find ways to talk to each other in ways that their oppressors won’t understand. Whether you’re Black or white, in the death camps or enslaved. People find a way to talk to each other that’s safe.

If you don’t think slave novels help us reckon with our past, do you think there is any hope for accountability?

I hope that no one thinks that my novel is about slavery. There’s a difference between writing a story about people who happen to be slaves and writing a story about slavery.

Do you think there comes a point in human suffering—especially the type James had to endure—where violence isn’t just an answer but the only just, retributive one?

The question is, “Is it violence when your life is threatened?”

You’ve famously said you know less after writing a novel. What do you know less about after writing James?

Well, if I could say that [then] I might know something.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.