No one knows how many Native American women and girls are missing and murdered each year. Yet everyone concedes there is a crisis, a “hidden epidemic,” as former Democratic senator Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota has called it. Although the federal government keeps data on virtually everything, it does not collect statistics on missing and murdered Native women and girls. It has no national database where tribes can report such crimes, no way for families or tribal investigators to seek information.

“The problem has been going on for hundreds of years with little or no intervention by the federal government,” Sarah Deer, a professor of women, gender, and sexuality studies at the University of Kansas, told me. “It’s getting attention now, but the problem is not new.”

Even without exact numbers, the statistics that do exist on the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’s (MMIW) crisis are staggering. In 2016, the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC), which tracks missing persons, pegged the total number of missing Native American and Alaska Native women and girls at 5,712. Yet this figure was undoubtedly low. Only 116 of these reports were logged into the Department of Justice’s federal missing persons’ database, a resource that allows law enforcement agencies to share information.

Although the 2015 Tribal Access Program (TAP) was supposed to effect tribes’ access to NCIC, that has been slow to happen. As of 2019, only 47 of the 573 federally recognized tribes in the United States were participating. That lack of access, due in part to the costs of updating computers, is critical. It means that many crimes go unreported, and tribal investigators who are called to a crime scene have a limited ability to pull up information on potential suspects. As a result, many cases go uninvestigated, unsolved.

The cost isn’t supposed to be a hurdle. The US Crime Victims Fund, a pot of billions of dollars drawn entirely from fines and penalties incurred by offenders, is intended to make resources available to local police forces for computer updates. It is also, significantly, supposed to pay for rehabilitation and preventive services, for victim compensation, and for victim services.

But every year tribes have had to fight for their share, mostly because they rely on states to disperse the money. According to a Department of Justice report released in 2017, “from 2010 through 2014, state governments passed only 0.5 percent of the available funds to programs serving tribal victims, leaving a significant unmet need in most tribal communities.”

Even those tribes with access to the NCIC database frequently don’t enter records. Native advocates say that a lack of staff is part of the problem. But there’s also a deeper, historical reason for the absence of reliable data. Distrust of law enforcement, fear they won’t be believed, that nothing will result, ensure many Native women and girls don’t report. The result is a climate of such pervasive unpunished crime that it is difficult to comprehend. In 2016, a report from the National Institute of Justice painted a jarring picture of this violence. Nationally, Native women are more than twice as likely to be raped or sexually assaulted as any other group of females in the country. On some reservations, Native women are murdered at more than ten times the national average. Nearly one in three Native American and Alaska Native women will experience rape or attempted rape in her lifetime. Native women also suffer intolerably high rates of physical violence—90 percent of it committed by non-Native intimate partners.

The reasons for this singular violence against Native women are complex. But they amount to, in essence, a level of racism so ancient and entrenched in America that it continues to poison how Native women are perceived today—as inferior exotic beings, as sexualized objects. “We’re targeted for who we are, what we represent, as Indian women and our sovereign nation,” Lisa Brunner, a member of the White Earth Ojibwe Nation, and co-director of the Indigenous Women’s Human Rights Collective, Inc., told me.

It doesn’t take much to conjure an example of this racist mentality. It saturates American culture, from fashion to sports, to seemingly benign childhood rituals like Halloween, when young non-Native women mindlessly don Pocahontas costumes. Native advocates with decades of experience helping victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, and sex trafficking have found these stereotypes to be not just offensive but exceedingly dangerous. “Oftentimes we get romanticized,” Brunner, who has repeatedly testified before Congress on the need to pass meaningful legislation to protect Native women and girls, said to me. “Victoria’s Secret plays a role in that. When you have models going down the runway wearing headdresses, it continues to foster that romanticism and increases the level of violence perpetuated against us.”

The crisis is also inextricably tied to the confusing matrix of laws governing Indian Country. “It is often perceived as easier to ‘get away’ with certain crimes on reservations because there is a lack of tribal policing and lack of tribal jurisdiction,” Cheryl Redhorse Bennett, an assistant professor of American Indian Studies at Arizona State University, told me. Although reservations are sovereign nations, the 1978 Supreme Court case Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe stripped tribes of their authority to punish non-Natives on tribal lands. This means that federal, tribal, and state agencies split jurisdiction. So when a crime occurs, it can be baffling to deter- mine who is supposed to be leading the investigation.

Say a Native woman is sexually assaulted. Where did it happen? On the reservation or off? If her attacker is Native and it occurred on the reservation, then tribal police and courts have jurisdiction. If her attacker is non-Native, then the FBI or state investigates. If she is assaulted off the reservation, the state is supposed to act.

As for felonies like murder, rape, and kidnapping, if they happen on tribal lands, the Department of Justice is supposed to prosecute. But the reality is the agency often doesn’t. In recent years, the Department of Justice has pursued prosecution in only about half of murder cases on reservations and in a little over a third of cases of sexual assault. In 2017, under mounting pressure to address this crisis, the department still declined more than one-third of the cases referred to them by reservation authorities.

But what of Native women and girls who go missing in American cities? More than 70 percent of American Indian and Alaska Natives live in urban enclaves, where crimes are investigated by local law enforcement authorities. Still, no one knows how many Native women and girls have disappeared or been murdered in cities in the United States, because there’s been little effort by police departments or other law enforcement agencies to keep track.

In 2018, Abigail Echo-Hawk, director of the Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) in Seattle, and Annita Lucchesi, a doctoral intern at the UIHI, tried to provide an answer. After contacting police departments in seventy- one cities across the country, they got a telling and sobering response. In their report, released that November, the Native American researchers found nearly 60 percent of police departments either did not respond to the request, or returned incomplete or faulty data. The indifference, the incompetence, didn’t end there. Some cities reported being unable to even identify Native victims. Others put down a woman’s race based on memory.

In several instances, cities couldn’t search for Native American, American Indian, or Alaskan Native victims within their databases because their computer systems simply weren’t built for it. The police department in Fargo, North Dakota, which has a fairly sizable Native American population, was typical. If a victim’s race was not indicated, the city’s record system “defaults to white,” the researchers were told. Other cities turned in data that confused Native Americans with Indian Americans, with surnames such as “Singh.” In some cases, police departments did not distinguish between missing or murdered victims.

With such shoddy police reporting, Echo-Hawk and Lucchesi turned elsewhere. They combed media outlets for accounts of missing and murdered women, and spoke with them about their reporting. They spoke with local Indigenous communities. As a result, they uncovered more than 150 missing and murdered women whom police had failed to identify.

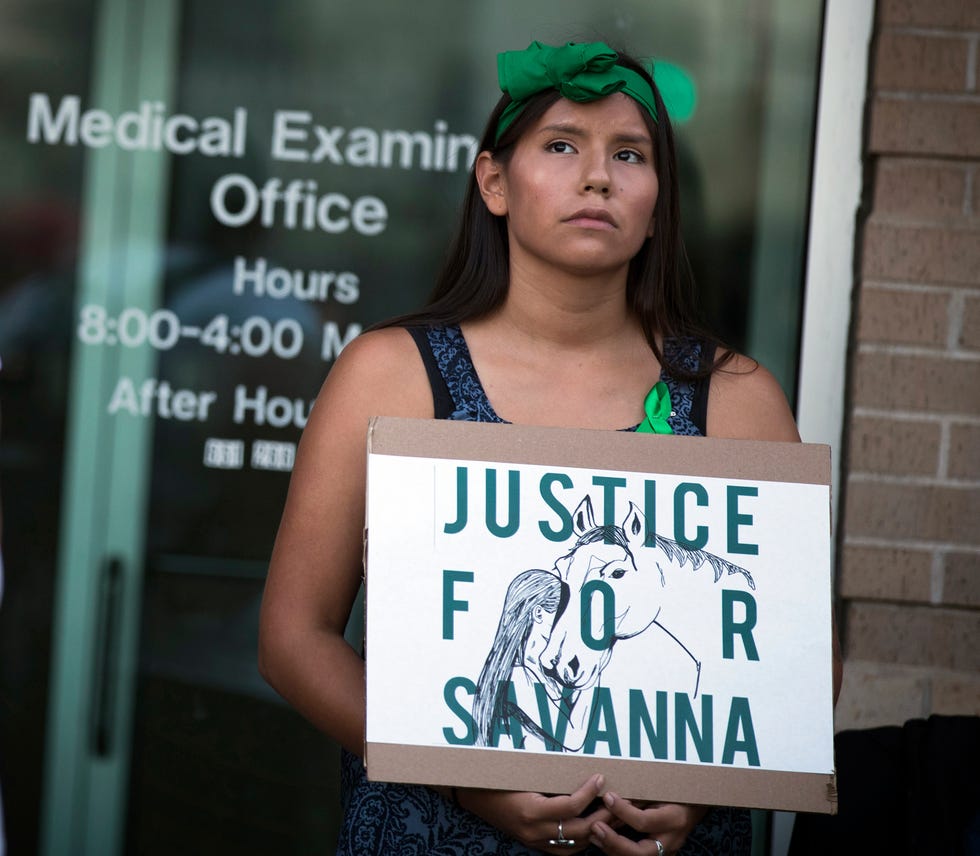

There’s a refrain you hear from Native American advocates about this stark invisibility. As the researchers wrote in their report, Indigenous women who are missing or murdered disappear not just once, but three times: “in life, in the media, in the data.”

My book, Searching for Savanna, is the story of one woman in one tribe, but her life and her death illuminate this ongoing crisis and the efforts by Native women to resolve it. Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, who was eight months pregnant when she was murdered, and all the missing and murdered Native women like her, deserve to be remembered and counted.

Adapted from the book Searching for Savanna: The Murder of One Native American Woman and the Violence Against the Many by Mona Gable. Copyright © 2023. Available from Atria Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Contributor

Mona Gable is a freelance journalist and author who specializes in travel, conservation, nature, culture and women. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Outside, the NY Times, Vogue, BBC Travel, Los Angeles magazine and many other publications.