Before they found the body behind their sorority house, four Delta Gamma Theta sisters went out for ice cream. It was a chilly Wednesday night in late April, but they’d just lost a debate competition, and visiting the Dairy Duchess meant avoiding homework a little bit longer. They were still finishing their cones a few minutes from Muskingum University’s New Concord, Ohio, campus when the conversation turned to their sorority sister Emile. Rumors she was pregnant had been swirling for months.

From the back seat, Emile’s roommate Jess* mentioned that Emile had been sick all day. She looked skinnier when the two went for dinner; the bathroom was a mess. Maybe she’d miscarried, someone suggested. Then a different idea surfaced. But if Emile had actually given birth, where was the baby? *(Pseudonyms, denoted with an asterisk, are used for students who declined to be interviewed for this story. With the exception of Emile, only first names are used for students who granted interviews.)

Elise had joined the sorority that semester and, conscious of being new, tried not to weigh in during conversations about Emile’s possible pregnancy. But she’s also the kind of person who prides herself on being helpful. So when the idea of checking the garbage came up, and Jess and Nicole* refused, Elise went with Samantha*.

The bins were empty, but a small trash bag was propped next to them. Oddly heavy and leaking fluid, the bag had been knotted so tightly that Elise and Samantha couldn’t untie it. Instead, they tore a hole in the plastic. Among an instant mac and cheese box, a freezer pop wrapper, and a Doritos bag, Samantha saw what looked like a foot. “I’m done,” she said, according to Elise. “I didn’t sign up to be in a sorority to do this.” It was dark, hard to see, and harder to believe.

The two fled back to the car, where Nicole, the sorority president, said they needed to know for sure. Reluctantly, Samantha and Elise rounded the house again. Using her phone’s flashlight, Elise peered inside, shifting the bag a bit. She fell to her knees, sobbing. “It’s a whole fucking baby,” she said.

Inside, other Deltas were making grim discoveries of their own. “Attention: Housemates, whoever made the mess in the study bathroom needs to clean it up ASAP,” Rachel*, the sorority house manager, wrote in a group text. “It looks like a murder scene,” she joked, before offering herself up as a resource in case anyone needed to talk. When a few other Deltas went to see what was wrong with the bathroom, they noticed something Rachel hadn’t.

Ashleigh was hanging out on the front porch with a friend from a nearby frat—unaware of what Elise and Samantha had found behind the house—when a Delta came out and described what she’d found in the bathroom. As the small group talked on the porch, an ambulance pulled onto the street. Oh, God, please don’t stop at our house, Ashleigh thought.

The Deltas were separated into different rooms. Ashleigh found a calm-seeming Emile upstairs. “I don’t know what’s going on, but I love you no matter what,” Ashleigh told her. Olivia, who also lived upstairs, first heard the pregnancy rumor a month prior and noticed Emile gaining weight, but only in her stomach. “Olivia,” Emile whispered, leaning out of her bedroom, “what’s going on?” Olivia didn’t know what to say, but together they crept from room to room watching the responding officers cordon off the house with crime scene tape. Soon, everyone except Emile was ushered outside of the house, spaced across the yard, and told to face the street. They couldn’t help but turn and watch as Emile was led away to a cop car.

There are few acts more disturbing than a parent killing his or her own child. Yet filicide, as it’s called, has persisted throughout human history, particularly affecting babies. In the Middle Ages, poverty and increasing stigma around illegitimacy contributed to a dramatic upswing, and “the sight of infant corpses lying in ditches, on garbage heaps, and in sewer drains was familiar throughout Europe,” according to historian David L. Ransel’s Mothers of Misery: Child Abandonment in Russia. Concerned with saving infant souls, the Catholic Church formalized the long-standing practice of accepting unwanted infants and created foundling hospitals and homes.

While public perception of killing a newborn has shifted over the centuries, it still occurs, albeit at much lower rates. In 1970, U.S. forensic psychiatrist Phillip J. Resnick, MD, argued that when a parent kills his or her baby in the 24-hour window after birth, the act is markedly different from deaths that occur at subsequent points in the child’s life. Neonaticides, as he termed them, are almost exclusively carried out by mothers, and unlike those who kill their children later, these women are much less likely to be psychotic or severely depressed.

Instead, as continuing research shows, they tend to be young, lacking in social support, ill-equipped to cope with a pregnancy, and driven by a toxic combination of fear and shame. They almost always give birth alone, having spent the previous nine months unable or unwilling to accept their pregnancies. In some cases, the newborn dies from what is effectively neglect, left unattended or improperly cared for. In other instances, the baby is asphyxiated, stabbed, or drowned.

Pre–Roe v. Wade, Resnick advocated for the liberalization of abortion laws. The relationship between abortion access and neonaticide isn’t entirely clear, but when we spoke, Resnick said that if abortion becomes unavailable or more difficult to access, he’d foresee an increase in neonaticides.

Today, pro-life state legislation has made getting an abortion virtually impossible in many regions. Ohio state officials have used a number of legal tactics to limit abortion access. Last April, the state passed a law banning abortion after six weeks, though a federal judge temporarily blocked it before it could go into effect. For young women, even when abortion is legally accessible, cost and parental notification laws impede its use. In one recent neonaticide case, a teen who suffocated her newborn told investigators she had considered getting an abortion but was too afraid her parents would find out.

With Americans’ deep ambivalence about non-procreative sex and female sexual desire, it’s not surprising that young women struggle to reveal their pregnancies. But it’s hard to understand how things develop to a point where an otherwise healthy person resorts to killing an infant or fails to care for one in such a way that the newborn dies.

Because many neonaticides go undetected, estimates of their prevalence in the United States vary widely, from about one neonaticide a week to 300 a year. Most young women who commit neonaticide give birth, clean up, and act as if nothing has happened. A corpse tucked into a dresser drawer or a patch of grass disturbed by a hasty burial is often the only sign that something has gone horribly wrong.

Upon setting foot on Muskingum’s campus as a freshman in 2013, Emile Weaver achieved something her mother Sandy Potts never had.

During sophomore year of high school, a classmate raped Sandy. “Don’t you know what happens to girls like you who are out late at night?” she recalls her mother asking when she got home. Sandy became depressed, suicidal, and reliant on alcohol to cope with the trauma. Desperate to leave, she finished her high school credits early. But her parents wouldn’t let her attend college until she turned 18, and while she waited, Sandy accidentally got pregnant with an older guy.

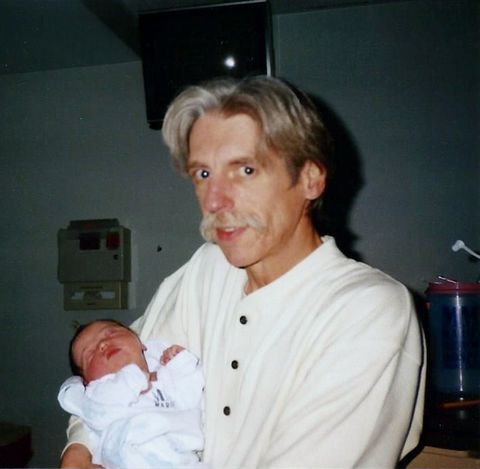

A few years later, as a single mom working at a discount department store, Sandy fell in love with her supervisor, a Vietnam veteran twice her age named Mike Weaver. By the time they had Emile on Christmas Day of 1994, Sandy was 22 and had three children under age four. When Emile was six months old, the family moved to a mobile home near the elementary school in Hannibal, Ohio, about 50 miles up the Ohio River from Sandy’s hometown. (They’d eventually relocate to a house in nearby Clarington.)

Sandy believes Mike had untreated PTSD, she told me he coped by drinking and working excessively and that he physically abused her but not the children. Emile remembers her parents fighting constantly and their small home filled with shouting. She developed anxiety early on, chewing on her sippy cups and biting her fingernails until they bled.

“I didn’t go into being a mom as an expert. I went into being a mom like, ‘I want to do things differently,’ ” Sandy told me. “Everybody has some type of being screwed up in their life…. And how do you not pass some of that on, even if you’re trying to change things?”

A psychotherapist would later describe their household as “authoritarian,” with spanking and the silent treatment meted out for infractions. In an attempt to offer her children information she’d never had, Sandy broached the topic of sex, only to find they knew about sexual acts she’d never heard of. The conversations made her blush.

Emile’s parents divorced when she was 10, and two years later, Mike died suddenly. Sandy had remarried, and Emile found her new stepfather controlling. She’d later tell a psychotherapist that he wrote his name on his groceries so no one else could eat them and refused to let anyone sit on his living-room couch because they could dent it. (He declined to be interviewed for this story.)

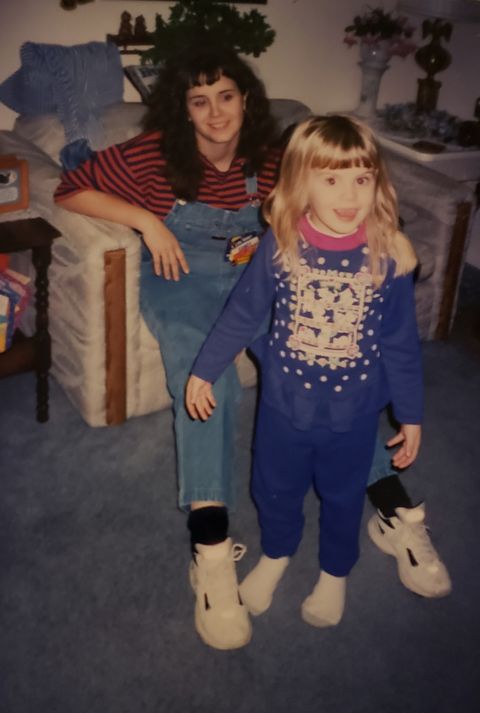

“We all just isolated into our rooms,” Emile explained. Meanwhile, an autoimmune disorder, repeated surgeries, and brain fog–inducing prescriptions rendered Sandy distracted and often unavailable during Emile’s teen years. Still, Emile was a high-achieving, popular student. She fell in love junior year and dated her high school boyfriend until they graduated.

Coming from a town with a population of about 384, Emile chose Muskingum for its small size and its navigable little campus, since she’s “horrible with directions.” She started as a chem major before deciding to switch to biology. Her freshman year Twitter feed is a testament to normal collegiate life: concern over a messy dorm room, complaints about 8 a.m. classes, and an affinity for naps. “All I do in college is homework and eat snacks #whatalife” one tweet reads.

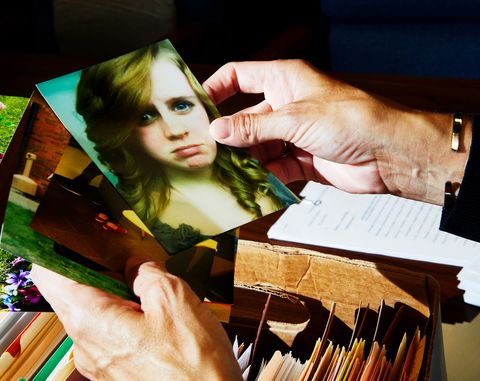

Emile rushed Delta in the fall. In photos, she is a slim, pretty blonde; deep-set eyes and frequently dilated pupils sometimes give her a frenzied look. Deltas described her as emotionally reserved but socially outgoing. She had a sharp sense of humor and was always up for the next party. Though described by some as occasionally hotheaded, friends found her considerate and kind.

In a crowded room, Emile was always the first to ask about someone’s day, according to Ashleigh. “She made you feel included no matter what,” Ashleigh told me. “There was a reason why she had a lot of friends in the house.” The sorority had around 30 members, but if you asked Emile or any of her sisters, “How many Deltas are there?” they would say, “One,” a numeric symbol of Delta unity.

Eleven years before Emile enrolled at Muskingum University, a student living on the same street at what was then called Muskingum College delivered a baby in her dorm, wrapped the newborn in a blanket, and put him in the trash. She told authorities she thought the baby was stillborn. According to her lawyer, she appeared to be suffering from pregnancy denial. After her interrogation was suppressed by a judge, she eventually took a plea deal. In exchange for pleading guilty to involuntary manslaughter, child endangerment, and abuse of a corpse, the prosecution agreed to not recommend a sentence. The judge sentenced her to three years; she served seven months.

Pregnancy denial is surprisingly common, affecting approximately 1 in 475 pregnancies at the 20-week mark, according to a 2011 review in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Though there is a psychotic subset, “it seems that external stresses and psychological conflicts about pregnancy may lead to denial in otherwise well-adjusted women,” the authors write. While denial can foreclose abortion by pushing the pregnancy past viability, the hostile environment around abortion may be one of the external stresses contributing to denial in the first place.

Pregnancy denial often resolves itself, only affecting 1 in 2,500 by delivery. Still, pregnancy denial should trigger referral for psychiatric assessment, the journal authors write, because its effects can be devastating. A woman who denies her pregnancy likely won’t bond with the fetus or prepare for delivery. Failing to go through the psychological and practical transformations of pregnancy increases the risk of insufficient prenatal care, dangerous and unexpected delivery, and neonaticide.

But not all women who commit neonaticide are unaware of their pregnancies; in fact, many spend months actively hiding it. “When you conceal a pregnancy from your entire family or the constellation of people around you, and when they buy into the concealment…everything in your universe is reinforcing your sense that this is just not happening,” says Michelle Oberman, a professor at Santa Clara University School of Law who has interviewed dozens of women who killed their children and coauthored two books on the subject. Some experts believe that women who are aware enough of a pregnancy to conceal it cannot be, by definition, in denial; others think it’s possible to move between different levels of awareness and denial throughout a pregnancy.

Premature delivery and lower infant birth weight are more likely among women in denial, which would make denied pregnancies less physically noticeable to friends and family. A woman concealing her pregnancy may eat less than is recommended in order to avoid weight gain.

Still, in many cases of neonaticide, at least one other person knew about the pregnancy or strongly suspected it. When those in the know fail to intervene, some experts believe it creates a dangerous feedback loop, strengthening the denial or enabling the concealment.

But no matter how similar they are, “[legally, if you have] knowledge [of the pregnancy], the system flips from knowledge into intention and calls it first-degree murder,” Oberman explains. While neonaticide in the United States can lead to lengthy prison sentences for murder, in many other nations, perpetrators often receive mental health treatment, community service mandates, or relatively short sentences for the equivalent of manslaughter. “I think Americans have a unique penchant for blaming individuals for societal or collective ills,” Oberman says. “It’s important to start by saying, ‘To be sure, [Emile] deserves some blame.’ The question is, How constructive is it to give her all the blame?”

Sophomore year started out full of promise. Emile was newly single. She moved into the Delta sorority house, living with her best friend, Jess, in a bedroom they painted pink. Less than two weeks after classes started, she went to Muskingum’s Wellness Center seeking birth control. Emile was given a routine pregnancy test; she’d get her prescription after it came back negative.

Emile had spent freshman year in a chaotic, on-again, off-again relationship with Ryan*, an athlete she met at a bonfire the first night of school. “I feel like I surrender to all my relationships,” Emile later told a psychotherapist. “I just feel like I don’t want to be alone.”

Emile would testify that Ryan was abusive. (He didn’t testify and declined to be interviewed for this story.) On the stand, Emile said Ryan would get drunk, push her around, and destroy her room—“you know, anything so he had the upper hand.” A friend of hers I spoke to recalled finding Emile crying in her trashed bedroom. A Delta interviewed by police said she believed he was verbally abusive.

Emile broke up with Ryan at the end of freshman year. Over the summer, she spent time with both Ryan and her high school boyfriend, whom she’d later describe as “the high school sweetheart who never went away.” By the fall, Emile and Ryan were officially over, and he was attending college in a different city.

In September, a voice mail and two emails asking Emile to visit the Wellness Center went unanswered. When Emile hadn’t responded a week later, the nurse consulted with the staff doctor and the director of the Wellness Center. They sent increasingly strongly worded texts and then a certified letter through campus mail. Five days later, Emile signed for an envelope containing her positive pregnancy test results. She never opened it. “I think I was scared,” Emile testified. “I felt like I didn’t want to know, so I just put it off.”

According to Oberman, from a legal standpoint, the school did its job. “But is that enough,” she asked, “when silence is so irregular that you’re sending a certified letter in the first place?” Muskingum did not respond to a question about whether the school had implemented any policy or procedure changes following the earlier neonaticide.

One weekend night in October, as Emile was coming down the stairs, she fell. Emile blamed the fall on drunkenness, but the way she fell without catching herself seemed weird to Carrie, who also lived in the Delta house. According to Carrie, over the next few weeks, she heard that other Deltas had seen Emile fall in a similar manner.

“Between her drinking…and her falling, we were honestly concerned about her because we weren’t sure if she was pregnant and trying to do something about it,” Carrie told me. (Emile said she’s fallen down stairs numerous times throughout her life, but never intentionally.)

Rachel, the house manager, knew Emile from home, where they’d played basketball against one another. On the stand, Rachel said she’d texted Emile before winter break to ask if she was pregnant, and Emile said no.

Emile acknowledged the pregnancy to one person—Ryan. According to her testimony, she wasn’t sure exactly when in the fall she told him she might be pregnant, but she remembers his response. “He wanted no part,” she’d later testify. “He acted, you know, like it was all my fault. He didn’t want me to tell anyone.… His reaction was, Baseball season was coming and that was his main priority and nothing else.”

One November weekend, Ryan drove to Muskingum’s campus to take Emile to an abortion clinic for a precounseling session. On their way to the clinic, an ice storm hit, and Emile and Ryan were turned around by the highway patrol. They never went again.

“I didn’t want to go alone, and Ryan told me baseball season was more important and that he had no other time,” Emile testified. Ryan told a detective “they never really discussed the abortion or even her pregnancy to any real deep extent after the ice storm,” even though they were in regular contact.

“I haven’t told anyone about this situation but it’s getting harder to keep quiet about,” Emile texted Ryan in March, according to texts obtained by authorities. “I don’t know what to do besides keep it a secret.” If Emile told her mother, she might call Ryan’s mom, a prospect that seemed to terrify him. (Police records suggest Ryan hadn’t told his parents about the pregnancy.)

Emile told Ryan she was afraid of getting fat, of “fucking [having] a kid” when she didn’t want to, and of another female student, whom she believed had hooked up with Ryan, finding out and telling everyone. (According to that student’s police statement, Ryan had already told her about Emile’s pregnancy when he visited in November.)

“I just don’t know how to deal with this situation,” she texted him. Ryan encouraged her to call or visit the abortion clinic, even after she said there wasn’t much they could do so far into the pregnancy. He then made another request—for a naked selfie, since she’d been his good luck charm for games.

In the spring, according to trial transcripts, Emile was turning down dinner invitations, sleeping more, and drinking less. The once sporadic rumors increased; they got “really bad” after spring break, Nicole testified, because Emile had “started to show.”

Another Delta would tell police she reached out to Emile several times that spring after hearing rumors and noticing Emile’s growing stomach. She didn’t directly ask about the pregnancy but offered support and inquired about Emile’s well-being. Emile responded that nothing was wrong.

In April, Rachel found Emile cooking hot dogs in the kitchen and tried again to ask. Before she could finish the question, Emile denied she was pregnant. Erin*, another sister who’d heard the rumor and noticed some changes to Emile’s behavior, also texted Emile to see if they could talk. When Emile cut her off, insisting she wasn’t pregnant, Erin wrote back “lmfao I know ur not babe” and suggested a female classmate of theirs was probably trying to “start shit” by spreading a rumor.

At a school of 2,500, Deltas said, pregnant students were rare. Emile remembered hearing about another pregnant student from her Delta sisters. “Each and every day I sat at a table with them, and they talked about her all the time, either her weight gain or, I mean, ‘I can’t believe she’s pregnant in college,’ ” she’d testify. “So I just didn’t want to tell them. I didn’t want to be that person that was even talked about.”

When the Deltas couldn’t get a satisfactory answer out of Emile, they tried using a Delta tradition to put her in a position where not drinking would be weird. At a party that spring, Taylor* and another Delta gave Emile a Straw-Ber-Rita, popped the tab, and sang the Delta song, after which the recipient is supposed to drink. “We were, like, kind of seeing if she was pregnant,” Taylor later testified. Emile took a tiny sip.

Like many sororities, Delta Gamma Theta produces an abundance of swag. Emile had been wearing baggy sweatshirts that semester, but when it was time for the annual Greek Week dodgeball tournament in April, she wore a custom design from Delta’s T-shirt committee. Dressed identically to her sisters, Emile stood out. “Rumors had already been going around, but now we’re in front of campus and the rest of Greek life competing in matching T-shirts,” Elise explained.

In an early game, Emile dodged a ball and fell hard. Sitting on the sideline, Elise and another Delta exchanged glances. “The look on our faces was kind of like, ‘Well, oh shit…that’s not good if she is pregnant,’ ” she told me. “And I kind of feel like that’s what everyone was thinking.”

Even if everyone was thinking it, there’s no indication in the trial record that anyone pulled Emile aside during the tournament. Rachel later said they included Emile in social activities so she wouldn’t feel isolated. Deltas I spoke to said they didn’t realize Emile was as far along as she was. Members of other sororities at the game believed Emile’s friends in Delta knew about the pregnancy, and some Deltas believed her mom did. Though Emile went home numerous times throughout the school year, including Easter weekend in early April, family members I spoke to said they didn’t notice the pregnancy.

Delta made it to the final round. It was Emile who made the winning catch, but she caught the hurtling ball right in her stomach. “It was a very bizarre moment,” Elise recalled. She was on the court right next to Emile and turned to share in Emile’s success. But Emile wasn’t excited; she seemed out of it. “I remember vividly just turning around and celebrating with someone else,” Elise said. A week later, Emile went into labor.

Taylor woke up at 7:30 on April 22, 2015 for an early class, and heard a screech like “a dying cat” followed by three or four cries. Tracing the noise, she walked around downstairs. From the empty study, she saw light beneath the door of the half bathroom, assumed the person using it was playing a game or watching a video on her phone, and went to take a shower.

As in 96 percent of neonaticide cases, Emile gave birth at home, close to others yet entirely alone. These are risky conditions for delivery: Even planned home births overseen by midwives are roughly 10 times more likely to result in a stillbirth than hospital deliveries, according to a 2013 study of 13 million U.S. births.

Women accused of neonaticide often claim the baby was stillborn, and although it sounds like a convenient excuse, it seems that home births both increase the risk of stillbirths and create an environment ripe for neonaticide, wherein a desperate, exhausted young woman gives birth to an otherwise unaccounted-for infant in a home where others are statistically likely to be present. In Emile’s case, the autopsy concluded the baby was born alive.

Emile’s account of what happened in the bathroom, aspects of which prosecutors dispute, is gruesome. She had stomach pain and diarrhea the night before—a bug going around campus, she thought. When she woke up that morning, she went to the study bathroom feeling like she needed to defecate.

“I felt some pressure lower, and that is when I realized that I was delivering my baby,” Emile testified. “I just pushed once and then the head and everything mostly came out. I think I helped with her shoulder, to help pull her out into the toilet.”

But Emile was distracted by what else was coming out of her: “I was bleeding really, really bad, and that’s when I noticed the placenta cord still in. I started to panic because I really didn’t know what to do.”

Delivering the placenta didn’t stop the bleeding, so she stuffed paper towels inside her vagina. Emile got a serrated knife from the kitchen—which Deltas later found sitting on a shelf in the bathroom—and cut the umbilical cord, then placed the baby facing upright in the bathroom’s trash pail.

The chief forensic pathologist would describe her as 6.6 pounds, 21 and a quarter inches long, and “pink and healthy looking.” At approximately 38 weeks, she wasn’t quite full term. There were no bruises, signs of strangulation, or stab wounds. He’d later testify she died from asphyxia.

Showering in another downstairs bathroom, Taylor could hear the study toilet flushing repeatedly—Emile trying to flush the “terrifying-looking” placenta down the toilet. “I just wanted it away. I just didn’t want to look at it anymore,” Emile said. The toilet clogged and overflowed. Exhausted and lightheaded, Emile lay down on the couch in the study.

As soon as she could stand again, Emile went back to the bathroom, frantic to clean everything up. Worried she might bleed to death, she set an alarm for several hours later to make sure that didn’t happen while she slept.

Around five o’clock, Emile and Jess went for dinner at McDonald’s. Emile drove. “She seemed fine, like mentally and emotionally fine, but she limped a lot to the car,” Jess said on the stand. Back in their room, the two watched TV until some Deltas arrived asking if anyone wanted to get ice cream. Jess went; Emile stayed behind.

Again, Emile confided in Ryan. “No more baby,” she texted, and then “Taken care of.”

“I would like to know how you killed my kid,” he replied after repeatedly asking what happened. At first, she refused to tell him—“You haven’t cared this whole time”—but then wrote that she’d given birth to a baby girl with his dark hair who’d died from placenta complications.

“Went by myself,” she told him, perhaps suggesting she’d gone to the hospital. She may have been lying, but Emile also texted something she thought was true: No one knew she’d given birth. When EMTs climbed the stairs a few minutes later, they found Emile sitting on her bed, cross-legged despite vaginal tears that would require stitches, working on a school paper.

When Sandy Potts arrived at the Muskingum University Police Department the next afternoon, she could smell her daughter’s blood. Sandy learned something happened after one of the Deltas messaged her on Facebook.

The previous night, before cops escorted Emile from the sorority house, Emile talked to a school administrator who’d shown up at the scene. They spent about five minutes together in Emile’s room. The administrator later testified that they “chatted about classes.”

Emile says none of the Muskingum staffers she saw that night encouraged her to go to the hospital, suggested she talk to a lawyer, or offered to accompany her to the station. (Citing privacy laws, a Muskingum University representative said he couldn’t comment on how university officials handled the case, adding, “We do take the responsibility of supporting our students, and cooperating with law enforcement, very seriously.”)

According to trial transcripts, over five interviews that lasted until 3:47 a.m., Emile confessed increasingly incriminating details, from claiming she hadn’t taken a pregnancy test to admitting she hadn’t had her period since October.

During the first interview, Emile said the baby didn’t make any noise. By the second, she said it was maybe breathing and moving; by the fourth that it was moving a little bit and making some noises. (Throughout the interviews, Emile maintained she hadn’t hurt her baby and that the baby wasn’t moving when placed in the garbage bag.)

Emile was bleeding heavily and spent breaks between interviews in the bathroom, restuffing her vagina with paper towels. She didn’t have her phone or wallet and had been told she couldn’t return to the sorority house. She says she slept on the floor in the station break room.

In a final interview the next day around noon, she acknowledged she’d been more focused on her own health than the baby but insisted she didn’t intentionally harm or kill her. If she was going to do that, she asked, why would she lift the baby’s head out of the toilet water instead of letting her drown?

In her videotaped confession, Emile seems bewildered by her own behavior, unable to understand why she hadn’t done more. “I didn’t do anything to it physically; obviously, I didn’t do much at all,” she said.

Emile went home to her mom’s house and crawled into bed. On April 25, 81 hours after Emile had given birth, Sandy took her to the hospital, where she was treated for an infection and excessive bleeding. Hospital notes indicate staffers initially thought she’d miscarried; when they discovered she’d given birth at almost full term, they called the police, who interviewed Emile at the hospital. Emile says the hospital didn’t provide or refer her to any mental health care; hospital records don’t suggest they did. A court-appointed psychologist later diagnosed Emile with PTSD, major depression, and panic disorder.

At home, Emile slept through the day and stayed up all night. In one late-night drawing made during this period, Emile is holding a newborn with angel wings and kissing her forehead. Sandy suggested that Emile give her daughter a name. Emile barely responded when Sandy threw out ideas, but after a few days, Emile shared her decision. She’d spent the night on baby name sites and had settled on Addison Grace.

Detectives determined the baby’s biological father was Emile’s high school boyfriend, not Ryan. Her high school boyfriend declined to be interviewed for this story. The officer who collected his DNA wrote, “He said he felt sorry for Emile, said she was a good person, and hoped a whole lot didn’t happen to her.” Addison was buried in a small cemetery overlooking the football field where her parents had graduated from high school two years earlier.

According to Deltas I interviewed, the day after Addison’s body was discovered, school administrators offered them new housing and a suggestion: Given the media attention, they might want to stop wearing their sorority letters. They accepted the living arrangement—11 sisters crammed into a six-person apartment so they wouldn’t have to split up—and rejected the advice. Wearing Delta letters became “like a shield,” Katrena told me, particularly when fellow students called them “baby killers” on an anonymous messaging app and insisted Emile couldn’t have acted alone.

Initially, some Deltas stood by Emile. The sorority always “felt like an actual family,” Katrena explained. “No matter what fight you were in yesterday, tomorrow if someone else is saying awful things about this person, she is your sister and you should have her back.”

That ethos usually applied to clashing personalities, but when Greek life site Total Sorority Move reported on Emile’s July arrest for aggravated murder, abuse of a corpse, and tampering with evidence, Elise tweeted, “That’s my sister and you do not know the half of it.”

Exchanging letters with her former roommate and best friend Jess during what would have been her junior year, Emile wrote as if she were studying abroad, not stuck in the county jail. She reminisced about late-night hijinks, weighed in on Delta drama, and looked forward to drinking her first legal beer. She seemed to believe she would get out, or could not bear to acknowledge the alternative.

The sorority sisters who walked into the Zanesville, Ohio, courtroom in May 2016 had been transformed over the past year. Many came with diagnoses of depression, PTSD, and/or anxiety. Elise developed a drinking problem in the weeks after discovering Addison’s body that took years to get under control. They’d also made a T-shirt to honor the support they found in one another following the tragedy. “When everything goes to hell, the people who stand by you without flinching—they are your family,” it said, but Emile’s place in the sisterhood was unclear.

According to Elise, while some of the Deltas were angry, she went into the trial trying to withhold judgment and give Emile the benefit of the doubt. When others referred to Emile as a monster or a murderer, Elise suggested that they wait to see what the trial revealed. She was hoping for an explanation, but didn’t find a satisfactory one. In the aftermath of the trial, Elise said she did “a 180” in her thinking on Emile. She also stopped calling Emile her sister. For Katrena, that moment came when she learned the baby had definitely been born alive.

During the trial, 11 Deltas testified to varying levels of awareness about Emile’s pregnancy and what they’d seen her do to hide it. “We were together most of the time, all the time,” Jess said on the stand.

“At the beginning of the year, she kind of made jokes to me about not changing in front of [me] or whatever, and then in the spring, she started to go to the bathroom to change her clothes.” She noticed Emile’s feet and ankles were swelling. Baggy sweatshirts were fitting progressively tighter, and Emile covered her stomach with a pillow or a blanket when

But Jess never asked Emile if she was pregnant. “I mean, I just didn’t want to offend my friend,” she testified. “Like if she wasn’t pregnant, I can’t say, ‘Well, you’re fat.’ ”

“Tough position,” the prosecutor noted. “Yeah,” Jess said. “And some people that were close to her, not as close to me, already asked her and she said no. So I felt that she would tell me the same thing.”

Neonaticide presents a challenge for any defense attorney. In Emile’s case, in addition to the testimony of her sorority sisters, numerous findings suggested that she knew she was pregnant. On her dresser, police discovered black cohosh, a natural supplement with a warning label on the bottle advising consumers not to take it if pregnant or nursing.

The chief forensic pathologist testified that he didn’t know much about black cohosh, but that women often use it for symptoms of menopause, PMS, or at the end of a pregnancy in order to induce contractions. (While in custody, Emile told detectives she took it in September for cramps.) It came out during the trial that there were only 20 pills left in the 100-count bottle Jess testified to seeing Emile buy two and a half weeks before she gave birth.

Although concealed and denied pregnancies can both produce deliveries with an elevated risk of infant mortality, how a jury interprets the defendant’s level of awareness can impact the outcome of the case. If a jury believes that a defendant didn’t know she was pregnant, they might view the baby’s death as a tragic accident. But if jurors think she knew about the pregnancy and was actively hiding it, it’s easier to see her as a liar willing to do anything to keep the pregnancy a secret.

“Mental health testimony helps to explain the critical issue in many of these cases—the ‘Why?’ behind it,” says Michael J. Benza, a senior instructor of law at Case Western Reserve’s law school, who is not involved in Emile’s case. Before the trial, Emile’s lawyer entered a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity. The judge ordered Emile evaluated, which resulted in two reports written by the same court-ordered psychologist that established her competency to stand trial and lack of severe mental disease or defect at the time of the offense. That court-ordered psychologist noted problems with anxiety and depression that, while undiagnosed, had likely emerged during childhood, with “both of these conditions worsen[ing] significantly” during the “latter part” of Emile’s pregnancy and into her subsequent delivery.

“Most striking in Ms. Weaver’s mental status at the time of the offenses is what appears to be an incredible denial of her situation,” she wrote. “There were some traits of dependent and paranoid personality disorders suggested,” but not enough for a diagnosis, she found.

For the trial, Emile was represented by a new attorney, R. Aaron Miller. (Miller also represented the 2003 defendant who was sentenced to three years.) At trial, Miller said Emile had lied and told “untruths”; she had “absolutely not” done the right thing in disposing of her baby. But he attacked the aggravated murder charge and disputed the prosecution’s suggestion that Addison suffocated in the garbage bag.

Emile did not kill her baby, he argued; she put her dead baby in the trash. The asphyxiation could have been caused by the way the baby was set down before being placed in the garbage bag, not due to a lack of oxygen in the bag itself, Miller suggested. He tried several tactics to dispute the autopsy findings.

Miller explained to the jury that Emile was young and afraid. Though the court-ordered psychologist had previously documented anxiety and depression in Emile, Miller didn’t introduce Emile’s mental health history to the jury and didn’t present any expert testimony on her mental health issues. Reached for comment, Miller says Ohio doesn’t allow for a diminished capacity defense; therefore, additional psychological evaluations wouldn’t be applicable.

Experts I spoke to about the use of mental health testimony in criminal law, none of whom were involved or reviewed in Emile’s case, offered differing opinions. Katherine H. Federle, a law professor at Ohio State University’s Moritz College of Law and the director of its Center for Interdisciplinary Law & Policy Studies, says it’s not possible to bring mental health testimony before a jury in criminal trials in Ohio unless those mental health issues rise to the level of insanity or are used to illustrate something unrelated to the defendant’s mental health.

But both Benza and Jim Hunt, who is an attorney, adjunct professor, and administrative director of the University of Cincinnati’s Weaver Institute for Law and Psychiatry, say that’s not always the case. They say that in Ohio criminal trials, it is sometimes possible to bring mental health testimony before a jury regarding a defendant’s issues with depression, anxiety disorders, and/or personality disorders, even when they don’t rise to the level of insanity.

Benza and Hunt note that while a defense lawyer may decide, for various reasons, not to pursue it, this kind of testimony can be very effective. While there’s disagreement over use during the trial phase, Benza, Federle, and Hunt all agree that these kinds of mental health issues could be introduced to the judge during sentencing.

The phenomenon of pregnancy denial didn’t come up at the trial. But when the prosecutor asked Emile what she thought would happen when the baby came, she answered, “I didn’t think…I didn’t think about the pregnancy. I denied it.” Asked why she hadn’t taken preparatory steps like buying diapers or baby clothes, she said, “Because I said no so many times that in my mind none of this was happening.”

After deliberating for an hour and eighteen minutes, the jury found Emile guilty on all counts. At the sentencing hearing, Miller asked for leniency, referring to “the greater issue of neonaticide” for the first time. He described an offense committed by “young girls” across the country and defined it as a “societal problem” but offered no further explanation. He didn’t bring up Emile’s mental health issues.

Given the opportunity to speak, Emile asked for forgiveness. “It is hard to find the words to say because I can’t forgive myself,” she said. Emile apologized to Addison for “the life she didn’t get to live” and to her sorority sisters for the “emotional suffering and negative publicity” she’d brought upon them. “I am especially sorry to Samantha and Elise, who found Addison and who can never forget those images.”

In his sentencing remarks, Judge Mark C. Fleegle read from letters several of Emile’s sorority sisters had submitted about how traumatized they’d been. The Deltas suffered daily, the judge said, and “unfortunately, there’s no charges for that.”

He also read from a letter Emile had written to him acknowledging her initial indifference to Addison. “In those four short paragraphs, you mention ‘I’ 15 times, and ‘my’ 5 times. Once again, it’s all about you.” On the charge of aggravated murder, he sentenced her to life without the possibility of parole.

According to Muskingum County prosecutors D. Michael Haddox and Ron Welch, Emile got off easy. They’d considered going for the death penalty. “We knew she was a young girl and we really didn’t think it was a case where a jury would reach a death verdict,” Haddox told me in December 2018. “And you know what: After we tried that case, I think they’d have given her a death penalty in a heartbeat. That’s the effect she had on the jury.”

Haddox and Welch described Emile as a self-obsessed liar and remorseless killer. The one time she cried during the trial, Haddox said, was when he asked whether she’d do to a puppy what she did to her own daughter. The word evil was tossed around. Welch, an assistant prosecutor, said he’s had two cases in which grand jurors returned to see the arraignment. The first was a woman who burned three people to death. The second was Emile.

Last April, the Deltas returned to Judge Fleegle’s courtroom on behalf of the prosecution as Emile fought for a lighter sentence. Months earlier, Ohio’s Fifth District Court of Appeals ordered Fleegle to hold a hearing to consider whether Miller had done enough to explain neonaticide, and its social and cultural causes, as a mitigating factor in her sentencing.

Emile’s new public defenders, including a trio who defend Ohio’s death row inmates, hired psychotherapist Diana Lynn Barnes, PsyD, to assess Emile and contextualize her actions. Barnes consults for the state of California on maternal mental health and has testified as an expert in many criminal cases involving neonaticide, pregnancy denial, and child abuse.

Slight and bespectacled, Barnes set out to articulate the simple idea that pregnancy doesn’t happen in a vacuum. In the process, she set off an emotional debate about blame, who deserves it, and how much. Barnes argued that Emile’s upbringing produced poor coping skills; a toxic romantic relationship exacerbated the situation; and the sorority sisters compounded her helplessness in handling an unwanted pregnancy.

“I’m not holding them at fault, nor am I blaming them for any failure to take action,” Barnes testified of Emile’s family and friends. “That’s not the issue here.” But the community’s inability to recognize the pregnancy or intervene did have an impact; according to Barnes, at the time, it functioned as “a reconfirmation for Emile that she [wasn’t] pregnant.”

But prosecutors attacked her analysis on a number of fronts and cast the expert as an outsider whose personal history of postpartum depression made her sympathetic to women who kill their children. Welch brought in one Delta after another to counter Emile’s claims about the sorority, as detailed in Barnes’s report, and show how compassionate they’d always been toward peers dealing with pregnancy and motherhood.

Among other examples, the Deltas said they’d warmly included another woman who joined the sorority with a three-year-old son. “We even let him wear [sorority] letters, which we don’t let anyone else [do],” Rachel testified. “You have to, you know, earn them.”

Another Delta was treated kindly after having a baby. It wasn’t entirely clear during the hearing that these two instances occurred after Emile’s arrest. The pregnant Delta, Elise later told me, gave birth the day Emile was sentenced. She went to the hospital for pain, delivered a baby she hadn’t known she was pregnant with, then didn’t return to school.

Interviewed by Barnes for her report, Emile called Delta a “harsh environment” and her sorority sisters “judgmental.” But Samantha pointed out that they’d stood by her even after April 22. “We supported her until the evidence gave us no choice but not to,” Samantha said on the stand. She then turned to Emile, who would not meet her gaze. “If we can support you after you murder somebody, why wouldn’t we support you for having a baby?”

For all the discussion about Emile’s environment, the focus remained on her sorority, not the larger university community. The Deltas had never dealt with a neonaticide, but the school had. Sitting in on the hearing, I wondered how the lessons from that earlier case could have shaped education for subsequent students. Muskingum did not respond to a question about whether the school had implemented changes to educational efforts following the earlier neonaticide.

As for the birth itself, Barnes testified that Emile dissociated while giving birth and wasn’t fully in control of her actions. On the stand, she argued that Emile “fluctuated” in and out of conscious awareness of the pregnancy, concealing and experiencing denial. After reflecting during her incarceration, Emile told Barnes she may have been attempting to miscarry by taking the black cohosh, but she drank and played dodgeball to fit in.

The prosecution raised concerns with aspects of Barnes’s methodology, and the judge didn’t appear convinced that denial and concealment could coincide. But Judge Fleegle also seemed to take issue with her qualifications—“She’s not a medical doctor,” he noted—and how Dr. Barnes’s personal history of postpartum depression could “bias” her work.

Fleegle might have preferred an expert like Resnick, who coined the term neonaticide. Unlike Barnes, Resnick is a medical doctor, and he tends to consider pregnancy denial and pregnancy concealment separate phenomena. He’s skeptical that women who commit neonaticide dissociate while giving birth. Still, Resnick is not a supporter of harsh sentences for neonaticide. So long as the neonaticide doesn’t go undiscovered, “the idea that they would endanger the community or a future infant is unlikely,” he told me. He’s never heard of a woman who was caught reoffending.

Ultimately, Fleegle wasn’t persuaded by the arguments of Emile’s new legal team and concluded that Miller did “the best he could.” Emile’s hopes weren’t high for a positive outcome, but it’s one thing to manage expectations and another to hear the judge uphold a sentence of life without parole. Hunched over because one wrist was handcuffed to her waist, Emile swiftly wiped away tears.

Two weeks later, I sat with Emile in a small children’s library at Dayton Correctional Institution used by incarcerated mothers hosting their visiting children. Picture books lined the shelves, and scribbled drawings were taped to the walls. It was a week before the four-year anniversary of Addison’s death, and trees flowered in the prison yard.

Emile wore pale blue eye shadow and mascara that smudged when she cried. One of the first things she wanted to clarify was how she feels about her sorority sisters. “I never wanted it to be like I ever blamed them for any of this,” she said. “They probably didn’t have much option to testify, but for them to just act like I was so heartless, that was what was hard.”

Looking back on sophomore year, Emile acknowledged she concealed her pregnancy and insisted she was in denial. She told people she wasn’t pregnant, and she thought they believed her. “I think it just started out, like, first just telling people no,” she said. “Them not really thinking I was pregnant…manifested into a bigger [belief]: ‘I’m really not pregnant.’ ”

Although desperate to avoid becoming the subject of gossip, Emile seemed to be begging for help, keeping the black cohosh bottle with a label reading “Menopause Support” out on her dresser. She walked around in front of her mom in a sports bra and shorts in March. “I think that whole time I just wanted somebody else to take control,” she said.

Through letters and phone calls, Sandy and Emile have learned how to communicate with each other, becoming closer in the process. Sandy endured the most recent hearing with pen poised, taking notes on the proceedings. She keeps a huge binder of documents, text messages, and photos that might help her daughter’s case.

One of the biggest misconceptions, according to Emile, is “[the idea] that I thought this through, that I just planned to go in a bathroom that day and that everything that played out is how I wanted it to be.” If people believed she wasn’t pregnant, she thought, she must not be far along. She felt the birth “was never going to happen.” Even in the study bathroom, she was shocked to pull a baby from her body. But then came the rushing blood and her panicked attempts to stop it.

Asked about the moment she realized her baby was dead, Emile struggled. There were “some movements,” at first, she said, but “I really wasn’t focused on her.” She considered Addison as an “it,” not a real baby.

Resnick told me this line of thinking is relatively common. “There is ordinarily a great attachment before the baby is born, and women who commit neonaticide do not form that attachment,” he explained. “It’s easier to kill the child because it is perceived as just some annoying thing…rather than their baby.” So what was Emile thinking about? “Um, that I just needed to clean up.”

It wasn’t until Emile was shopping for a burial outfit at Babies“R”Us that Addison became real to her. Surrounded by bibs and bottles, Emile broke down, sobbing. “How did you feel?” I asked. Emile paused. “Like a monster.” Her nightmares have ebbed, but dealing with her period often triggers flashbacks to the study bathroom.

For years, Elise couldn’t use black garbage bags; they reminded her too much of finding Addison. But when her roommate accidentally bought a box last winter, she found she could use them without panicking until the box ran out and she bought white bags again. When Emile’s conviction was upheld, Elise felt relief. A few Deltas I spoke to believe Emile’s initial sentence was too harsh, but there’s a pervading sense that justice has been served.

In the spring of what would have been Emile’s junior year, the Deltas held a color run to raise awareness for safe havens, now an annual tradition. Safe haven laws, passed in every state between 1999 and 2009, give women the right to anonymously relinquish their newborns. These laws represent the U.S.’s biggest response to neonaticide, but they were passed in most states without funding stipulations. Emile and a number of her sorority sisters told me they’d never heard of safe havens, and the detective who interviewed Ryan wrote that “he indicated surprise when told Emile could have simply dropped the baby off at a police or fire station and walked away without giving her name.”

While safe haven sites do get used, their national implementation hasn’t curbed neonaticide in the way supporters hoped it would, in part because they’re logistically challenging for the population particularly vulnerable to neonaticide.

“How does a mother get from the locked bathroom in her parents’ house to the safe haven without being seen or without the infant being heard?” law professor Carol Sanger writes in the Columbia Law Review. “Does she take a bus or subway or borrow the family car? What does she use to transport the baby?” Critics say addressing neonaticide after the birth is too little, too late.

Today, Emile’s sisters live in city condos or houses in their hometowns; some are engaged, and a few have already gotten married. They work as nurses or teachers or are considering going back to school.

Because of her sentence, Emile hasn’t been able to take college classes to finish her degree, but a recent policy change means serving life without parole no longer disqualifies her. She hopes to enroll as soon as she’s able to. She’s worked in the prison library, tutored a bit, and taken advantage of whatever educational opportunities she can find.

Emile believes she should be punished, but considers her sentence extreme. (It will likely cost the state of Ohio over $1,500,000 to incarcerate her.) While her former sorority sisters move forward, for Emile, there is an endless sentence and her endurance of it. But she brightened when I asked about an appeal. “I definitely do have hope,” she said.

The day after our interview, the local news reported on the case of a high school senior in a nearby county who gave birth two days after prom to a baby she said was stillborn. In September, the jury found her not guilty of aggravated murder, involuntary manslaughter, and child endangerment. She was found guilty of gross abuse of a corpse, and the judge sentenced her to seven days in jail (which she’d already served) and three years’ probation. She’d buried the baby in her parents’ backyard.